How much do you know about the heart, the muscular organ responsible for pumping oxygen and nutrient-rich blood all through the body?[1]

One of the powerhouses of the body, the heart beats 100,000 times per day, pumping around 2000 gallons of blood each day. Once your heart stops beating, you are dead. Thus, it is extremely necessary to take proper care of your heart. High levels of cholesterol are risky for the body since it can lead to heart failure. Experts recommend following a proper diet and a healthy lifestyle to keep your heart healthy.[2]

As long as your heart is healthy, you are healthy. Slight complications will eventually lead to severe risks.

How does blood travel from the heart?

The heart is made of ventricles and arteries. The heart pumps blood through the combination of blood vessels, referred to as the circulatory system. The blood vessels are elastic tubes responsible for carrying blood from the heart to other parts of the body.

Blood is a functional part of the body. Apart from bringing nutrient-rich products to body parts, it is also responsible for carrying waste products such as carbon dioxide away from body tissues. Needless to say, blood is one of the essential requirements for a healthy, sustainable life. It is responsible for the healthy functioning of body tissues.

Blood vessels are usually of three types: arteries, capillaries and veins.

Arteries: The arteries start at the aorta, and the larger one leaves the heart. The arteries are responsible for carrying blood to body tissues. These eventually turn into branches, becoming smaller to move far away from the heart and reach other body parts.[3]

Veins: Veins take the unpurified blood to heart. The blood that reaches the heart isn’t rich in oxygen. Unlike capillaries, veins become larger when reaching the heart. The superior vena cava is the largest vein and brings blood from head and arms. The inferior vena cava is responsible for bringing blood from the abdomen and legs.

Capillaries: Capillaries connect the veins and arteries. Since they have thin walls, waste products can easily pass through them in the organ’s cells.[4]

Did you know that the combination of veins, capillaries and arteries is around 60,000 miles long? The blood flows in a continuous motion around your body. The proper working of these arteries, veins, and capillaries make it effective for the heart to pump blood.

Where is the heart located?

Often it is said that the heart is located on the left side. But, actually, the heart is placed under the rib cage slightly on the left of the sternum between the lungs.

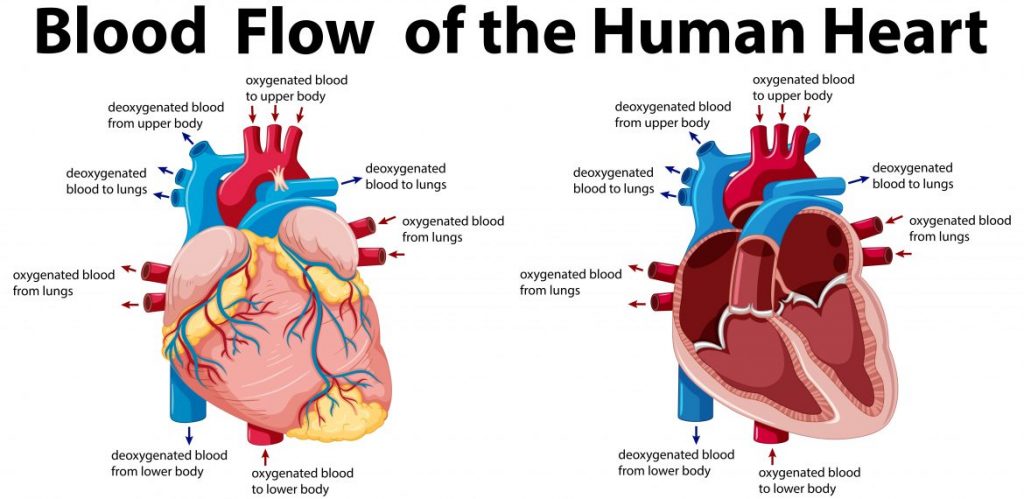

The diagram of the heart makes it clear to be made up of muscles. The strong muscular walls of the heart are responsible for the contraction and relaxation of the heart. All the major blood vessels are responsible for connecting the heart to other body parts.[5]

The heart is a hollow organ from inside made up of different chambers. The left and right side of the wall is divided each other called septum. The upper chambers of the heart are referred to as atria (receiving blood from veins), and the lower chambers are known as ventricles (pumping blood to arteries).

The atria and ventricles work in coordination with each other to pump blood. When blood leaves the heart, it passes through different valves (mitral, tricuspid, pulmonic and aortic valves)

The heart valves function the same way as the valves in our home. The valves are responsible for preventing the blood from going into the wrong direction.[6]

How does blood flow through the heart?

Both the right and left sides of the heart need to work properly. The coordination between the two helps to pump blood to the right parts.

Right side

- Blood enters the heart via the superior and inferior vena cava. The oxygen-devoid blood is emptied in the right atrium.

- The contraction of the atrium leads the blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle via the tricuspid valve.

- Once the atrium has emptied the blood into the ventricle, the valve closes to avoid the backflow of blood.[7]

- On the contraction of the ventricle, blood enters the pulmonary heart via the pulmonic valve. Then the blood enters the lungs to complete the oxygenation process.

Left side

- The oxygen-rich blood from the lungs enters the left atrium via pulmonary veins.

- On atrium contraction, the blood shifts from the left atrium to the left ventricle through the mitral valve.

- The mitral valve closes when the ventricle is full.

- On contraction of the ventricle, blood leaves the heart to enter the aorta via the aortic valve and eventually is transported to body parts.

How does heartbeat happen?

The atria and ventricles work contract and relax alternatively to make the blood flow.[8]

The electric impulses of the body give way to the heartbeat.

The impulse begins in the sinoatrial node (specialized bundle of small cells) in the right atrium. It is also compared to a natural pacemaker. The impulse spreads across the walls of atria, thereby leading to contraction.

The AV node that is located between atria and ventricles slowers the electrical impulses before it gets into the ventricles. The slight delay allows atria to contract before ventricles.

The pathway of fibres, referred to as His-Purkinje network, allows the muscular walls of ventricles to contract due to the impulses.[9]

A healthy heart beats 50-99 times a minute. However, if you have indulged in heavy exercise, or are suffering from fever and are on medication, your heart will beat for more than 100 times a minute.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470256/

[2] Borelli G.A. History of Cardiology. Medical Life Press; New York, NY, USA: 1927. [Google Scholar]

[3] Robb J.S., Robb R.C. The normal heart: Anatomy and physiology of the structural units. Am. Heart J. 1942;23:455–467. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(42)90291-6. [CrossRef]

[4] Grant R.P. Notes on the muscular architecture of the left ventricle. Circulation. 1965;32:301–308. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.32.2.301. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1571338/

[6] Thomas J.D., Popovic Z.B. Assessment of left ventricular function by cardiac ultrasound. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;48:2012–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.071. [PubMed]

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279249/

[8] Rushmer R.F., Crystal D.K., Wagner C. The functional anatomy of ventricular contraction. Circ. Res. 1953;1:162–170. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.1.2.162. [PubMed] [CrossRef]